Science Communication Through Art: The Universal Language

Three different media of artistic expression help to bridge the gap between the public and scientific information.

This article follows the events at our inaugural #SCCSymposium, during which we re-examined the goals of science communication, our roles in society as science communicators, and the ways in which we can communicate. We sought to question and critically discuss the ways science communication is done and to integrate non-traditional media and social justice in our practices.

by Sophia Brynne Tuch

Graphic by Darren K. Cheng

Image Description: Hand-drawn illustrations of a pen, a zine, a podcasting microphone, and pins on a teal, tan, and white patterned background. Text reads, “Communication Media: Bridging art and science through different media.”

Science communication hosts a broad spectrum of varied media to reach wide audiences through different styles of communication. While these media differ immensely, many encompass one overarching component: art. Artistic drive, creative vision, and technique are all utilised in different forms to help best produce unique products capable of reaching the public in effective ways. The SciComm Collective Symposium showcased some of the artistic media used by science communicators and how these individuals created art for effective science communication. Dr. Christine Liu (she/her) and Tera Johnson (she/her) of Two Photon Art discussed their development of scientific art merchandise and zines; Kim Fahner (she/her) led a workshop highlighting the beauty of the natural world through ecopoetry; and Dr. Asma Bashir (she/her) spoke of her experience in the science communication community, as well as the community she fostered through her podcast, Her Royal Science.

Physical Media

Dr. Christine Liu and Tera Johnson, cofounders of Two Photon Art, began day two of the SciComm Collective Symposium by discussing how they broke into visual art media and science communication. Both met at the University of California, Berkeley, where Liu graduated with a PhD in Neuroscience and where Johnson is currently completing her Master’s degree in City Planning and Landscape Architecture.

Liu pointed to the creation of the duo’s first zine – a “DIY art booklet” on the volcanic activity in Nicaragua – as the beginning of their partnership. Zines take the form of a short, self-published magazine, often showcasing art or writing. Liu notes that they are a widely accessible form of communication due to their self-published nature. After their first zine festival, starting with only $50 worth of materials, the duo found that art, in the form of zines, colouring books, and stickers, connected with their audience in ways past science teachers never could. Art, especially interactive media, made science more accessible to a general audience. Their creations easily commanded attention by showing the beauty of the natural world and allowed for personal connections to be made between the audience and the subject.

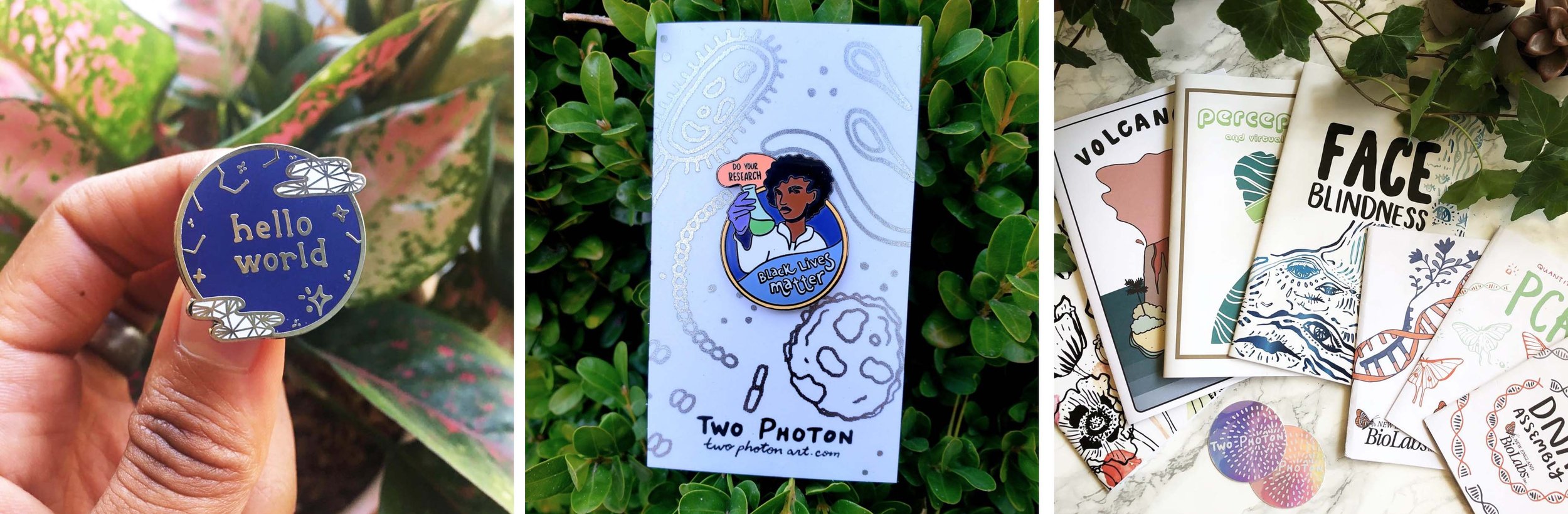

Two Photon Art also discovered that individuals did not just like being invited to engage science by consuming art, but also liked using art to express scientific topics that mattered to them. Liu and Johnson found that the creation of enamel pins met this market. They made the jump into pin-making during the “March for Science” era, when the push for truthful discussion on scientific topics was at an all-time high. Individuals were also seeking out forms of self-expression during a time in which the validity of different identities in STEM were being questioned. By partnering with several organisations, different demographics were able to brandish causes or topics that were important to them. Young girls interested in computer science had a Girls Who Code “hello world” pin, with the iconic phrase silhouetted by constellations, set in hard enamel. Black women scientists were represented in a pin made for The Loveland Foundation, in which a Black woman is holding an Erlenmeyer flask and saying “do your research” while “Black Lives Matter” fills out the bottom half. Two Photon Art’s storefront also includes pins engaging in several different fields – from computer coding to biological sciences. These pins provide a wide range of self-expression for those engaged in STEM fields, as well as those simply interested in the topics represented.

For five years, the duo has worked together to make a sizeable impact on their community through their art. They’ve created opportunities for other artists through their small grants program – sparking new creative endeavours with their own money – and by partnering with Massive Science to sponsor a program to train new science writers from marginalised backgrounds. Liu and Johnson, while starting from humble beginnings, have made it a mission to inspire others to make their own art and present the world of science through their medium.

Images Courtesy of Two Photon Art’s Instagram page.

Image Description: (Left) Hand holding a blue and silver pin with constellation designs and the text “hello world.” (Centre) Pin of a Black woman holding an Erlenmeyer flask and the text “Black Lives Matter” and “Do Your Research.” (Right) A series of colourful zine covers and stickers that cover various science topics.

The Written Verse

Kim Fahner directed the attention of the discussion towards a written medium: poetry. As Poet Laureate for the City of Greater Sudbury (2016-2018), Fahner writes poetry inspired by the natural world, where she is often swimming, hiking, and canoeing. She expressed both her love for the natural world and poets’ love for helping convey it, citing poems such as William Wordsworth with “Daffodils” and William Butler Yeats with “Lake Isle of Innisfree.” While she explains that she is not a scientist, her poetry and example of style portray a medium that can help make science a more accessible topic through shared human experiences.

Fahner explains that humans are primally connected to nature, making it a common muse for art. Even now in the modern era, nature is often the subject of our social media posts. While these online formats don’t resonate with Fahner as a poet, they encapsulate how humans are still deeply fascinated with the natural world around us. We are always seeking to understand it.

Similarly, one of the main goals of science is to understand the natural world and how it works from our observations. Both science and poetry work to encapsulate the human experience – individual and generalised –into something communicable to others. A poem uses techniques like sensory imagery, personification, simile, and metaphor to break down complex topics or visuals and relay them to the human mind. Similarly, science communication strives to dissect jargon-dense and inaccessible scientific writing. Literary techniques used in poetry are also found in science communication, with similar objectives of relaying complex topics in simple and creative ways. Fahner’s nature poetry, and the poems she encouraged the audience to write, exemplifies the blend between understanding the beauty of the natural world and conveying it to an audience in a succinct and beautiful way.

Fahner also noted that, historically, poetry has been a field dominated by white, cisgender men. Names like Whitman, Wordsworth, Frost, and Shakespeare are easily recognisable by the greater public, even when their poetry was written through the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. One of the most famous Black women poets, Maya Angelou, only became famous in the 1970s. With time, more women, 2SLGBTQIA+ folks, Black and Indigenous people, and people of colour have been recognised for their contributions. Today, emerging writers of all backgrounds express their own experiences through poetry, helping to fashion a more inclusive, diverse, and intersectional space for the medium.

This parallels the same story for individuals welcomed into science and science communication. There are ongoing discussions on how to better improve the spaces that science inhabits for those who were previously, or are currently, excluded. Science education has done so by correcting the historical accounts of women like Henrietta Lacks and Rosalind Franklin, properly acknowledging their contributions to science after their stories were hidden by white, cisgender men.

Poetry and science communication share the goal of breaking down historical barriers. In both fields, it is with many diverse perspectives that we get the truest version of how we communicate about the natural world.

Audio Description: Kim Fahner reading her poem “Outskirts.” Swim out into a northern lake, / just beyond the city limits, / and then hear that maybe / there’s a blue green algae bloom / after you’re already in the water. / Just don’t put your head under. / People swim here all the time, / have for years, so one bloom / is the same as the next, / and the health unit doesn’t have jurisdiction— / not here, not anymore. / If you don’t swallow any water, / and you don’t rub your eyes, / then you’ll be fine. / In the midst of it all, / you breaststroke through constellations / of blue green algae, the bloom / parting around you as you swim, / tiny galaxies exploding at elbows & knees, / so scattered, trailing in your wake.

Community on the Air

Dr. Asma Bashir brought the event to a close with the question, “What’s your story?” As a Black, Muslim woman with a doctorate in Neuroscience from the University of British Columbia, Bashir explained how her background shaped her experiences in academia. She commented on how she felt the need to explain herself more frequently than her peers. Why was she in science? What was her role in a space so dominated by white, Anglo-Saxon men? It was this questioning that led her to start her podcast, Her Royal Science.

On the Her Royal Science website, Bashir attributes the creation of the podcast to her love of meaningful conversations. She actively strives to have these conversations with minoritised groups in science. Bashir discussed her time in “academicomm” (academic communication), where she participated in initiatives that helped improve empathy, compassion, and understanding in the academic community. She aims to do the same when she asks interviewees, “What have you experienced?” during her episodes. The answers bring varied and unique viewpoints of the scientific world to an audience that gains to learn from different, intersectional experiences.

This is the human element of science communication that bridges the realms of science and art. During the Symposium, Bashir quoted Episode 14 of her podcast with Dr. Morgan Coburn, a disabled scientist. Coburn remarked, “Science, I think, is very divorced from your human person. People will praise the mind and meanwhile, their bodies suffer.” While the discussion was about Coburn’s health and the strenuous nature of a scientific career, Bashir expanded on how the field of science is divorced from the human experience and realistic expectations. Most branches of STEM have work environments that are not fully accommodating, leaving unhealthy performance expectations for all individuals to meet. For disabled persons, this appears as work environments and expectations that are not built with accessibility in mind. To reach her intended audience of other academics and call to light the lack of inclusivity and accessibility in STEM, Bashir uses the artistic process and presentation of her podcast. It is through the artistic craft of spoken word and podcast production that each of her interviewees are heard and understood by a wider audience. Without the human connection that art inspires, the message would lose its core principle of uplifting diverse human voices.

The human condition is often forgotten in STEM, but the inherently human element of communication is required to sustain it. Art in the form of Her Royal Science reminds us of that fact and re-inspires humanity within the communities of academic spaces. It reminds us to better ourselves and our spaces for the diverse humans who occupy them.

Widget Description: Soundcloud of Bashir’s Her Royal Science podcast. Find transcripts of episodes here.

Two Languages; One World

Science communicators, no matter their medium, use artistic concepts, skills, and practices. Artistic and scientific methods of communication are inherently intertwined. Science strives to comprehend the natural processes we observe and communicate them effectively to both students and researchers alike. It inspires continued efforts in understanding the natural world. Art strives to comprehend the vision of the artist, one that is deeply entwined with their personhood, and to represent their lived experience in this world. To break down the science into its “elemental units,” as Bashir described, and to explain it in one’s own words is to place artistic merit on it. It is a craft to better represent concepts not easily understood by the vast majority. It gives the public a starting place to engage with science: to drive new interests or promote a better understanding of the natural world. In the ever-evolving, diversifying field of science communication, art is the bridge gap between science and the public, and serves as a vehicle to better represent the voices of those who are excluded in science. As printed on a Two Photon Art enamel pin, written on an easel and surrounded by flowers, art supplies, and a round-bottomed flask: “Science is Creative.”

Author Bio

Sophia Brynne Tuch (they/she)

Sophia is a student at McGill University in her third year, studying Microbiology and Immunology with a minor in Communications. They are a digital artist and writer, particularly focused on digital illustration and scientific communications. She hails from Los Angeles, California, but now lives in Montreal while studying at McGill as a proud Canadian-American citizen. They hope to help bridge the gap and make clearer the innate connections between art and science. You can find them and some of their art on Twitter @sbrynne_t or contact them sophia.b.tuch@gmail.com.